|

|

|

Photos

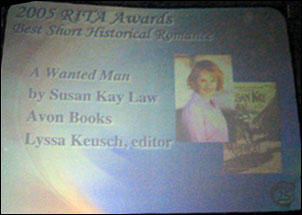

from the RITA

Awards,

|

|

||

|

|

|||

![]()

It's been five or six books since I've written a real villian. Having a bad guy running around driving the plot seemed like the easy way out. But this time I found myself in the mood for an out and out western, with a true villian and a hero tough enough to bring him down. Another chunk of the story came from several writer friends, who gently (hah!) informed me that the hero needed a much more personal stake in ending the villian's plans than I'd orginally envisioned. Most of the rest of the plot spun off from there, and so we've got a hero and heroine from very different worlds. On the surface of things they couldn't be more different. But the surface doesn't really have all that much to do with what goes on down deep where it matters, does it? Seeing what's beneath the masks we all wear and falling head over heels in love with what you find there is a common theme in many of my stories and A Wanted Man is no exception. --Susan |

| top |

![]()

Hell's

Pass, Wyoming It was a hard thing to lose a friend. It was harder yet when you could number your friends using less than one hand. When, if it came right down to it, it took but one finger. The fact that Sam Duncan called no one else friend was his own choice. It was a lesson he'd learned hard; when people around you dropped like flies in August it was far easier to remain alone than to get to know someone just to lose them. But Griff . . . Griff had been the one who, just like Sam, hadn't died. He didn't know if they'd been too lucky or too stubborn or just too damn stupid to give in when everybody else had. Though he had to admit ‘friend' didn't really cover it. When you'd spent nearly half a year together in a hole too small for a grave and managed not to kill each other you had a bond that most people – the lucky ones who skipped through life happily unaware of the really vicious things people could do to each other – could never understand. He winced, gingerly probing his jaw where it throbbed to beat hell, despite the ice he'd slapped on it an hour ago when he'd finally stumbled into Hell's Pass, Wyoming and found himself a saloon full of people who barely blinked an eye when a fellow wove in looking like John L. Sullivan, the Boston Strongboy, had used him for a sparring partner. Sooner or later he was going to have to wash out the blood matting his beard but he was shooting for later. It would have been closer when he'd crawled away from the Silver Spur to head to Salt Lake City. But that was a Mormon town and he'd known he was going to need a place where he could get some whiskey. He downed another slug from the bottle on the table before him, noting that his hand only quivered a bit when he lifted it. The room was small and rough, and the saloonkeeper had charged him too much for it because it usually rented by the hour. But Sam knew that once he dropped into bed he wasn't going to be able to crawl out again for a good twelve hours. Outside the single grimy window the sky had grayed, as if the sun were too tired to keep shining; not going out in a burst of flashy color, but simply fading away like a harlot's henna when her hair had gotten too gray to soak up the red anymore. A piano squawked from the main room below. He supposed it was supposed to sound gay and cheerful but instead it was brassy and off-tune, setting his brain to throbbing behind his eyes. Now and then a spurt of laughter – nasty-edged, the laughter of someone trying too hard to convince themselves they were having fun – burst through and clashed with the tune. He was obviously getting too old to have the shit beaten out of him. He felt every wound: the bruise that spread over half his chest and made him groan every time he moved, the kick that had caught him in the back, the swollen and split knuckles he'd earned trying to fight back. He couldn't open his left eye, and the fact that his knees still worked was nothing short of a miracle. He didn't recall it hurting so much. Maybe a fellow was allotted only so much pain tolerance for his life and he'd used his up before he'd hit twenty, because he was doing a piss-poor job of tolerating the pain at the moment. He contemplated the whiskey for a while. He had to work up to another drink, because the stuff set his split lip afire every time he touched it, a burn that was almost as bad as all the other aches combined. Maybe if he just didn't move, didn't twitch, didn't breathe, it'd be okay. Lord, if anybody could see him now . . . ow, ow, ow . Chuckling was a really bad idea, he quickly discovered. But really – he'd spent all these years building up a reputation as a really vicious piece of work, so much so that the mere rumor that he'd been hired had snuffed more than one strike and range war before they'd ever gotten started, and right now he doubted he could defend himself against a six-year-old. Yeah,

there'd been

a lot of men

coming at him.

Maybe a dozen,

he thought,

though his vision

had blurred

early on and

that just might

be his pride

talking. And

they'd caught But Sam hadn't gotten to be the highest paid hired gun in seven states by taking anybody's word for anything. He'd nosed around the nearest town for a bit – no information to be had, the most close-mouthed bunch of ostensibly “friendly” people he'd ever met, and that did make him suspicious – before heading back toward the Silver Spur. They were waiting for him before he'd ever gotten close . . . and since there were at least four other routes he could have taken back, he wondered just how many men Haw Crocker, the owner of the Silver Spur, had sent out to make sure that Sam Duncan regretted it if he didn't go quietly on his way. It had gotten dark enough in the room that he could no longer read the two papers he'd spread out on the rickety pine table. He gritted his teeth against the pain of moving his arm and nudged the lamp closer. The first one, small and crumpled even though Sam had done his best to smooth it out, he didn't need the light to read because he knew it by heart: the last letter he'd received from Griff Judah. They didn't see each often, not in years. Didn't need to – it was enough to know the other one was out there, alive and whole. Once in a while they wandered into the same town at the same time and spent a day or two in a place very much like this one, trying to prove to themselves and the world that, yeah, they'd survived, plunging into wild sprees that never seemed to be as much fun as they'd sounded no matter how hard they pretended they were. But Griff's luck hadn't run as good as Sam's after they'd left Andersonville. He hadn't gotten his strength back as quickly. And, while Sam's six-shooters soon became as much a part of him as his hands, Griff would just as soon have never seen a gun again. Sam had tried to help him out more than once – he had more money than he knew what to do with, considering he had nothing and no one else he cared to spend it on – but Griff had too much pride for that. But in Griff's last letter he'd sounded hopeful. Excited that he'd finally found a job that he might settle into. Haw Crocker's Silver Spur was the biggest, richest ranch between Denver and San Francisco and there was plenty of opportunity for a fellow to get ahead. It was the biggest and richest, of course, because the vein of silver Crocker had discovered had allowed him to buy up another fifty thousand acres and hand-pick the finest stock from Texas to Wyoming. Rumor had it, Griff wrote, that the mine still produced darn near eight hundred thousand dollars of ore a month, and wasn't that something? Not that he was interested in the mine. They'd both had more than enough of holes in the ground. But Griff liked the wide open spaces where the mountains flattened into a broad valley, and the cows and the horses and the fact that a man could work alone with them most of time. And all that silver could run a lot of cattle for a long time, couldn't it? But then Sam had never heard from him again. Griff had been pretty regular in his correspondence if nothing else and when two months passed without a word Sam had sent his own letter to the Silver Spur. Six weeks later the unopened envelope, ragged as if it'd had a hard journey, showed back up, NOT AT THIS ADDRESS printed in hard black letters across the front. So Sam had finished his current assignment – roust up a gang of bank robbers that the sheriff of Mill City hadn't been able to handle himself – and headed for Utah, straight for that unsatisfying visit to the Silver Spur and his brutal little meeting with the men who were supposed to ensure he didn't return and snoop around. Not

that they would

scare him off.

But it wouldn't

hurt to heal

up a bit first,

he thought,

and lifted the

bottle again,

noting a bit

hazily that

it was only

half-full. The

pain was finally He squinted at the newspaper he'd picked up on the stage to Hell's Pass. The driver had balked at taking on a man who'd looked like he'd just escaped from hell instead of wanting to be driven there, but a wad of cash and pretending to be a tenderfoot traveler who gotten in over his head had done the trick. Sam'd called himself Artemus Kirkwood, a pansy-assed name appropriate for a fellow dumb enough to get himself clobbered. He offered an outrageous amount to get the coach to himself, then stretched out on the seat and passed out for the first couple of hours. When he woke up, the now-friendly driver, undoubtedly eyeing a hefty tip from his clueless passenger, had offered him a copy of the Utah Register. Not much interested in anybody else's troubles at the time, Sam had intended only to give it a quick scan before using it to block out the vicious sun that had interrupted his nap. Instead, his gaze snagged on a headline halfway down page 1.

May 12. Sam calculated the distance between Hell's Pass and Omaha, pondered his own healing rate, and winced. It was going to be a damned painful trip. Planting both hands on the table, he pushed himself to his feet and swayed there for a blessed moment before going in search of some wash water. With any luck, Miss Hamilton liked her men a little rough around the edges.

END

OF CHAPTER

ONE Get

notified of

all future

book releases. |

|

| top | |

HUGE

NEWS:

HUGE

NEWS: